How to Feed Bees in Layens Horizontal Hives

LAYENS FEEDERS, HIVES, and FOUNDATION AVAILABLE FROM OUR STORE >>

Hives include all frames, fully assembled & ready to go

Feeding bees might sound like a trivial matter — fill a feeder with syrup and drop it into the hive — but in reality it is one of the biggest decisions you’ll make as a beekeeper. Before talking about feeder models, what to feed, how, how much, and when — let’s take a look at why we feed bees, so you can make an informed choice.

WHY FEED BEES (Inconvenient Truth)

Humans have been harvesting honey and keeping bees for thousands of years, but feeding bees is a very recent development. Feeding bees, so common today, looked totally nuts just a few decades ago (see Honey from the Earth, p. 197). Why do we feed bees? All three reasons are quite sinister:

1. Tremendous habitat loss. Until mere 150 years ago bees had such an abundance of natural forage that many beekeepers owned thousands of hives — and bees were finding enough flowers to stay well fed and to produce huge crops of surplus honey. Honey was cheaper than sugar; its supply seemed inexhaustible, with per capita consumption many times higher than today, while diabetes was a rare disease. Today — forget the gigantic apiaries of old — if you can put just 50 hives in the same spot, it’s considered good foraging ground; some states have laws requiring 2 miles between apiaries, because there are not enough flowers to go around. Honey production and use are in serious decline, while sugar consumption and diabetes rates are through the roof. So by far the best way to “feed the bees” is to restore the beautiful blossoming landscapes bursting with life and nectar. This is why we’ve created a thousand-acre bee sanctuary in the Ozarks (thank you for your support!) so bees can continue to thrive in a living, nurturing environment, and produce fabulous wilderness honey without any sugar feeding.

2. Using non-local bees. Bees can produce enough honey to share even in the most challenging environments (even deserts) — but only if they are adapted to local conditions. A strain of bees taken from its native environment and planted in a completely different climate will be struggling — it has no idea when plants will bloom, for how long, and in what abundance; how long and how harsh a winter to expect, etc. Say you bought Italian bees (native to the mild Mediterranean climate with a very long blooming period) — they are programmed to expect abundant nectar from spring till autumn, and if your location is not as favorable you will have to feed them due to the mismatch between their genetics and local conditions and flower availability. This is why Layens was warning against the use of Italian (and any other non-local) honeybees (see Keeping Bees in Horizontal Hives, section 242). Set out a few swarm traps, start your apiary with local wild swarms, and they will feed you instead of the other way around!

3. Beekeepers’ greed. Local bees will gather sufficient honey reserves to last them year round. This much is obvious — if bees living in nature weren’t able to provide for themselves, they simply would not exist. So why would anybody need to feed them? The answer, of course, is that many beekeepers don’t just harvest surplus honey (what bees can’t consume themselves) but also a good part — or all — of the wintering reserves bees need for survival. Once you do that, you must feed them sugar to avoid starvation, and problems begin (discussed in detail in Keeping Bees with a Smile). Sugar is cheap, and honey is expensive, so overharvesting honey for sale, even sacrificing bees’ health in the process, “makes economic sense.” This is in stark contrast to the old practices when beekeepers were leaving plentiful honey in the hive and even stored a large reserve of capped comb honey to give back to the bees in case of need (see Keeping Bees in Horizontal Hives, sec. 125 on how much honey to leave, and sec. 168 on how much to store in reserve).

So feeding bees sugar can be totally avoided with good and honest beekeeping practices. In natural beekeeping, feeding bees syrup may be done in an emergency as the last resort, but overdo it, and you join the throngs of beekeepers converting sugar syrup into “honey” — because yes, that sugar ends up in the honey as well. Then why bother keeping bees at all? You can buy honey that tastes like syrup (and that is syrup) at any supermarket.

HOW TO FEED BEES

Again, populate your hives with wild local swarms; put them in a wilderness habitat rich in blooming plants (or plant acres of bee forage yourself); leave plentiful honey reserves in the hive — and you’ll rarely, if ever, have to feed your bees. In the rare cases when you do have to feed, here are some suggestions:

What to feed to your bees

Honey is best food

The best food for the bees is their own honey and pollen, so storing a reserve of capped honey frames (Keeping Bees in Horizontal Hives, sec. 168) is a very good policy. In this case, just add a frame to a swarm or colony in need and you are done.

Extracted honey in a feeder

If you feed bees extracted honey, it’s better to reconstitute it with water: 1 part water : 2 or 3 parts honey, by weight.

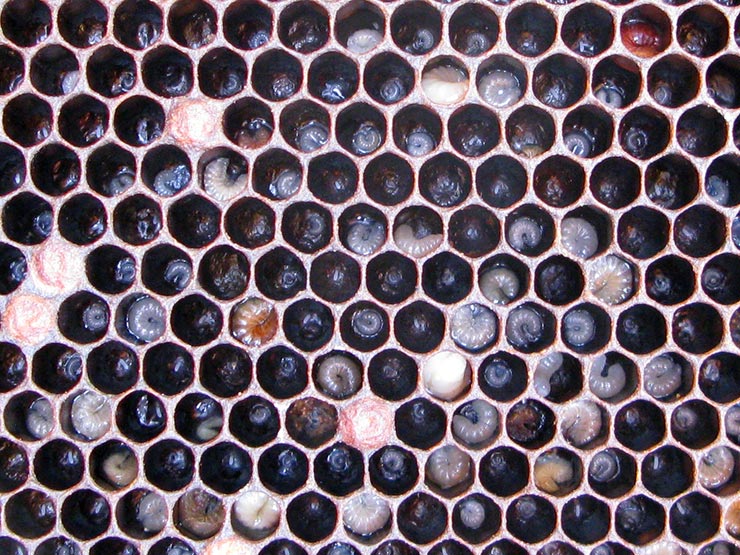

Honey must be from disease-free hives

However, you can only feed bees honey if you are certain it comes from hives that are free of infectious disease. For example, the bacteria causing European foulbrood can survive many years in honey. This honey is safe for humans to consume, but give it to your bees and you reintroduce this nasty infection. So feed your bees your own honey only if your apiaries have been free of foulbrood for the last few years.

Note that even if one hive in the apiary had foulbrood, honey from nearby hives falls under suspicion because of shared equipment and because the bacteria may be present in the hive and honey without visible disease symptoms.

Buying honey on the market to give to your bees is a very unsafe proposition, especially if you cannot talk to the actual beekeeper. Even then, be aware that many beekeepers give their bees antibiotics, which masks the symptoms without killing all the bacteria.

When I was first starting to keep bees in the Ozarks, I purchased some honey from another Missouri beekeeper plus some organic honey from the store (figuring that commercial honey would still make better bee food than sugar). I think this is how I first introduced European foulbrood into my hives, and after all these years the infection still occasionally crops up in my apiaries.

So unless you have your own honey from healthy hives (or know a trustworthy treatment-free beekeeper to buy honey from) do not feed your bees honey. Note that if your hive perished from viruses transmitted by varroa mites, this comb and honey can be safely reused in other hives.

Organic sugar syrup — how to make

If you do not have honey from zero-foulbrood apiaries, feeding bees organic sugar syrup is a much safer option than honey of unknown origin. A typical ratio of sugar to water is 1:1 (by weight). Add sugar to hot water so it dissolves faster, cool down to room temperature, then add (optional) one drop of anise essential oil to a gallon of feed to make it more attractive to the bees.

When to feed your bees

If you use local bees and leave them enough honey for wintering, spring development, and summer dearth you may only need to feed 1) natural or artificial swarms, 2) hives that are light in the fall, and 3) in case of complete honey crop failure.

Feeding swarms and artificial swarms (splits)

When you catch a swarm, look at the weather forecast. If the weather is warm, sunny, and flowers are in bloom, you don’t need to feed the swarm as they will find plentiful food in nature. Likewise, when you make an artificial swarm, you normally give it at least one frame of honey from the parent hive, and with favorable weather they will start foraging straight away.

But if the forecast shows cold or rainy weather for a week ahead, a swarm may starve, and you will save the bees by giving them some food.

Feeding hives that don’t have sufficient reserves in the fall

During honey harvest, estimate the weight of honey in the hive, and if the hive is low on reserves, simply add frames harvested from other hives that have surplus (see Keeping Bees in Horizontal Hives, sec. 125). Note that if the hive is too light, it’s better to just combine it with another hive. Taxing the rich to help the poor is the opposite of what you want to do in a successful natural apiary.

Feeding hives after a particularly poor season

If, after a particularly poor season, you have not pulled any honey but the hives are still too light to last the winter, you may need to combine hives and/or feed to boost their winter reserves. I’ve never seen as bad a year as that, but books have accounts of years of complete honey crop failure. Note that in nature, a year of scarce forage tests the colonies’ ability to stay small, frugal, and survive even under these extreme conditions. But it is also true that in nature, established colonies can draw on the previous year’s stockpile of honey to carry them through a poor year — so you’ll need to return to them what you had previously borrowed. A reserve of capped honey frames is particularly handy for that. Also note that small colonies have smaller food requirements, and I’ve successfully overwintered small colonies on just three Layens combs with barely 10 lb of honey.

How much to feed your bees

Feeding swarms and artificial swarms

Keeping Bees with a Smile (2nd edition, p. 324) has solid advice on feeding swarms. Basically, if the weather is nice and there is plentiful nectar, you don’t have to feed at all. Otherwise 2 quarts of feed (about 6–7 lb) is usually enough, except under very unfavorable weather then an additional feeding of 2 quarts may be necessary.

An artificial swarm (Keeping Bees in Horizontal Hives, sec. 163) would receive a similar amount of food either as a full frame of honey and pollen from the parent colony, or in a feeder.

Feeding package bees

WE DO NOT RECOMMEND PACKAGE BEES AT ALL. They are expensive, have low disease resistance, they are not locally adapted or acclimated, heavily depend on sugar feeding and medications, have low survival rates, and help destroy the local honeybee populations by producing drones to mate with local queens, thus diluting their locally-adapted genetics and ruining local colonies. If you buy a package, you unleash unprovoked drone warfare on the local population of bees!

If you get package bees, follow the conventional recommendations on feeding (which is a lot — commonly gallons — and may last on and off throughout the season) and treat them against the mites. You purchased a semi-domesticated animal and you need to give it the care you’d give domesticated livestock that is totally dependent on you instead of being robust and self-reliant. With all the additional care you’ll give them, there is still no guarantee the colony will even live to be one year old, but one thing is certain: the honey these bees produce will be laced with sugar and chemicals from varroa treatments.

Feeding light hives in the fall

The amount of honey reserves a colony needs depends on the climate (the length and severity of winter, and the uncertainty of spring weather), on the amount of insulation in your hives (in the north, colonies in well insulated hives will consume much less honey), and on the local adaptation of bees (local bees will be more frugal than southern bees planted in the north). For a strong colony of local bees in insulated hives Layens recommended leaving 35 lb in honey reserves (see Keeping Bees in Horizontal Hives, sec. 125) and I found it totally sufficient for our winters in the Ozarks of southern Missouri (Zone 6). Because of our very uncertain spring weather (it can get cold or rainy for many weeks on end) I try to keep 12 lb of honey per hive as reserve (1.5 frames), but this reserve it unused most of the years.

Frame feeder — the best feeder for Layens hives

The frame feeder is the best feeder for Layens hives. Its advantages:

- Compatible. The feeder has the same length as the Layens frame so it can be easily used in Layens horizontal hives.

- Accessible. In cold weather, the bees cluster in the top of the nest and are reluctant to go down for their food. If it stays cold long enough, they may actually starve to death with a bottom/entrance feeder full of food under the frames. The frame feeder gives access to food in the top of the nest, and is always accessible to the bees even during colder nights in the spring.

- Safe for bees and beekeepers. The ribbed walls give bees a better grip so few will drown in syrup. Made in Europe of food-grade plastic.

- Three compartments allow adding feed without taking the feeder out of the hive and without drowning any bees (see below).

Frame feeder — how to use

Keeping Bees with a Smile (2nd ed., p. 197) and Keeping Bees in Horizontal Hives (sections 109, 126, 127, 140, 141, 231) are full of good advice on feeding (and, more importantly, on avoiding the need of feeding through correct management of your hives). Here are a few tips based on these great books:

- Close to the bees. Put the feeder against the last frame with bees on it. Add a drop of anise or peppermint essential oil per gallon of feed to make it more attractive to the bees.

- Prevent robbing. When feeding smaller colonies during dearth (e.g., early swarms in the spring), give feed at nightfall, and only as much as they can consume overnight (about 2 cups for a small colony). Since robbers can’t fly at night and by the morning the feed is consumed, the risk of robbing is minimal. Narrowing down the entrance during feeding is another good step. Adding feed at nightfall has another advantage: the bees are calmer and don’t bustle as much; few, if any, bees get pushed into the syrup to drown.

- Alternate compartments. The feeder is internally divided into three compartments that allow adding feed without drowning the bees. The first night, add 2 cups to the first compartment. The second night some bees may still be busy in compartment one, so pour feed into the second compartment that will be free of bees. On day three, use the third compartment. By day four, if you need to continue feeding, add feed to the first compartment — by that time it has been cleaned up and has no bees.

- Cover the liquid feed with slices of cork, some straw or wood chips to serve as floats so bees don’t drown.

- Remove the feeder when you are done feeding so bees don’t build comb on it.

LAYENS FEEDERS, HIVES & MORE AVAILABLE FROM OUR STORE >>

Hives include all frames, fully assembled & ready to go

Many more guides are in progress, so please join our email list below for more free advice and important updates (no spam; only 2-4 emails per year, and you can unsubscribe at any time). THANK YOU! – we’re working hard to bring you the bees... and the smile!

— Dr. Leo Sharashkin, Editor of “Keeping Bees With a Smile”